Becoming an uncancellable witness

Reviewing Life in the Negative World by Aaron Renn

For the sons of this world are more shrewd in dealing with their own generation than the sons of light. And I tell you, make friends for yourselves by means of unrighteous wealth, so that when it fails they may receive you into the eternal dwellings. If then you have not been faithful with the unrighteous wealth, who will entrust to you the true riches?

Luke 16:8-9,11, ESV Catholic ed.

When I was leading theology and medicine seminars in Philadelphia, one question we struggled with as medical trainees was how our finances and settings of practice and had moral significance. Aaron M. Renn’s work appeared in most semesters of our two-year curriculum to bridge the gap between moral-theological foundations and on-the-ground practice. So, it’s fitting that my new foray into writing mention his newly released book, Life in the Negative World. Christians and moral conservatives will benefit from its insights, which warn against mission drift and advise adopting the strategies of a moral or cultural minority.

Renn’s book builds on a model featured in several of his essays such as his 2022 First Things article. The model describes different phases of relationships between Christianity and the surrounding culture during Christianity’s decline in the West, from the 1960s to today.

Initially, identifying and acting as Christian garnered status in elite settings. This situation gave way to neutral and now negative perceptions towards Christianity, such that holding and practicing Christian ideals now damages one’s social standing. Each of these eras saw its own cultural engagement strategies emerge. The era of positive perception featured strategies such as “culture war,” whereas prominent Evangelical figures in the neutral era preferred a “faithful presence” approach.

The latter approach, typified by pastors like Tim Keller and practitioners like Francis Collins, aimed to place Evangelicals in semi-elite positions as a Christian presence. Such Christians minimized conflict with secular culture and emphasized Christianity’s fulfillment of or agreement with that culture. While successful at gaining some converts, “faithful presence” has attracted criticism for frequent moral compromise and for accelerating policies hostile to Christian ideals. These approaches are largely ineffective now that the culture is explicitly post-Christian, but no new approaches have emerged for this current era.

As one studying religion and its social effects, I’ve observed these trends in cultural strategies with interest and am thankful for Renn’s analysis. After all, Evangelicalism has been the dominant expression of American religion the past few decades. Any changes in the movement will affect the cultural environment and even the health of all Americans. More personally, as a Catholic former Baptist with many Evangelical friends, part of me will likely stay Evangelical at heart, and our moral communities continue to have much to learn from each other.

Feeding the mouth that bites you

I’d venture that more than in any other profession, Christians in medicine exemplify the neutral world elite strategy and furthermore share the Evangelical discomfort towards “the very idea of elite-ness” (77). We seek elite positions but refuse to identify as elites with elite responsibility (noblesse oblige). Medicine predictably draws a large number of Christians and other altruists high in the conscientiousness personality trait. Conscientious but typically low- or medium-openness professionals like physicians, engineers, and sometimes even professors like to focus on the nitty-gritty. They leave questions of vision to their executives and administrators whose numbers have mushroomed.

Many of us believe that by adhering to a strong work ethic and a prescribed career course, we’ll achieve financial security while living meaningfully and helping others. We work hard and keep our heads down. Supposing that it doesn’t matter under what practice structure we operate, we choose the most convenient options. Hence the majority of professionals choose to be employees in cosmopolitan settings rather than exercise local leadership.

In so doing, we offer crucial labor to hospital conglomerates, academic centers, and multinational corporations run by people hostile to Christian morality. Such organizations stifle competition, promote procedures destructive to bodily and psychological integrity, and lobby for abortion and other issues opposed to our moral communities. Contributing to these institutions undermines our own interests and the common good. As Renn argues, Christians should consider revoking their institutional investment and redirect their energies to strengthening their own communities’ integrity.

Minority strategies

Renn offers a number of practical strategies to promote integrity at the familial, community, and institutional levels while mitigating the “negative consequences of living in a lower-trust society” (161). Essentially, these are strategies for becoming uncancellable. Those unworried about losing sources of income from being fired or sued will be much more likely to live out biblical marriage, educate their children as they wish, or advocate historical Christian positions on controversial issues. Example strategies include FIRE (financial independence, retire early), pursuing ownership of real estate and means of production, and high-trust business networks based on familiarity and local excellence as opposed to faceless global meritocracy:

Ownership of assets—institutions like schools, our economic life, social and cultural space, and even real estate—will be increasingly important for evangelicals in a world where the mainstream institutions of society are both degrading in their competence and increasingly hostile toward evangelical values (Life in the Negative World, 142).

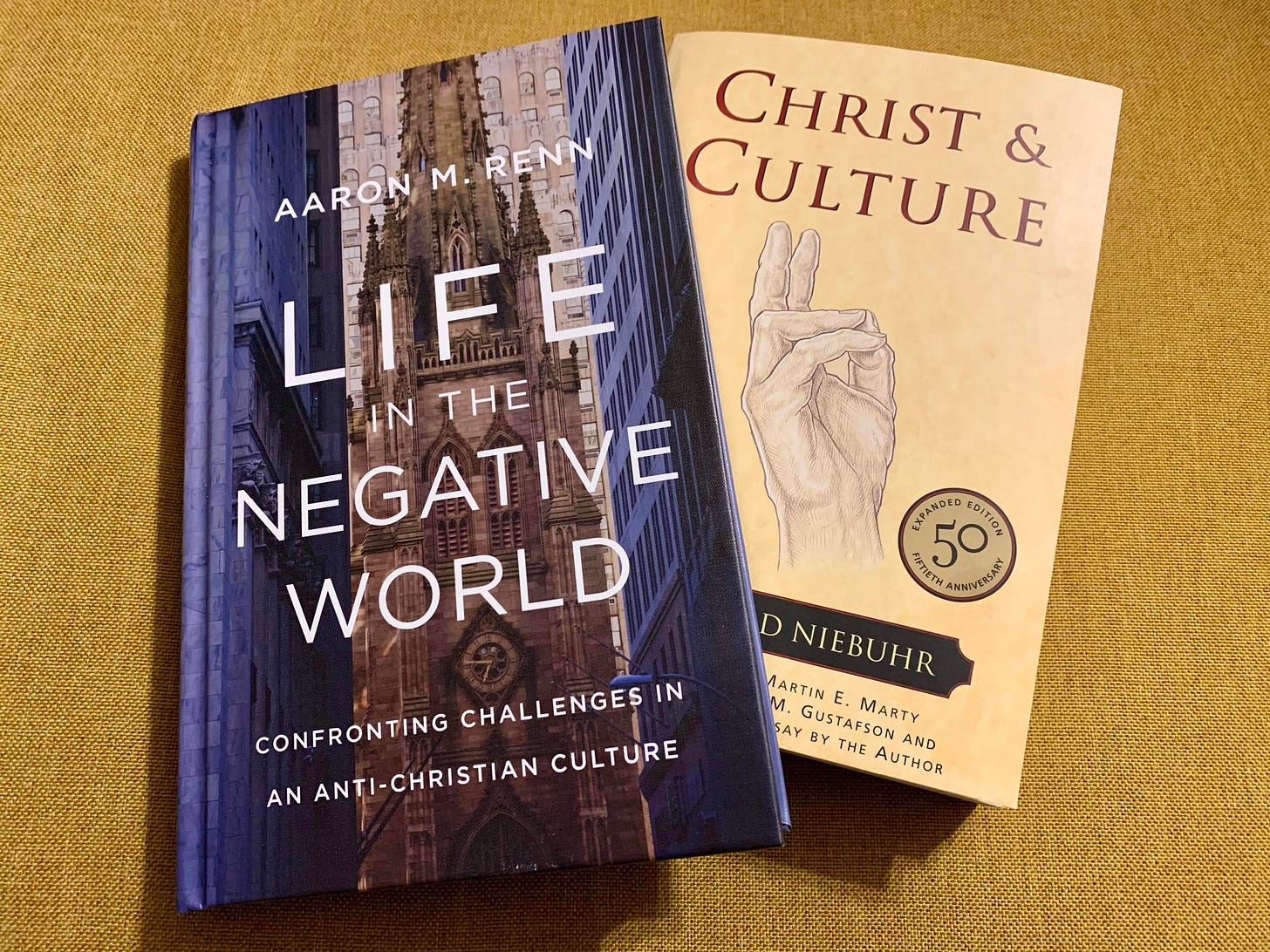

Many of these approaches were previously unknown to many Evangelicals. Therefore, some of these strategies could have been better fleshed out in the main text, although there’s great value in the notes section. Renn leaves much more controversial information, such as data on intersexual dynamics and singleness in churches, in these references. Since he already included many Bible references, I do wish he’d ventured into some theological analysis to give the book more lasting appeal. He briefly mentions H. Richard Niebuhr’s Christ and Culture, which I re-read alongside the book and found helpful for demonstrating the theological “end game” of each cultural strategy.

Renn borrows from other traditions (Catholics, Jews, Orthodox) to develop Evangelical strategies. He likewise could’ve offered constructive criticism for how social conservatives from those or other traditions could learn from Evangelical strengths. He pulls punches when mentioning other groups’ political strategies, such as the Catholic avoidance of grassroots work in favor of top-down rulings, which resulted in poor outcomes for the pro-life movement (see 46).

This diplomatic tone of writing has been consistent over the past few years and is still commendable, and many may prefer how the book’s overall style reads as an extension of his newsletter. Many of his recommendations apply to moral and cultural minorities in general and will be useful to a diverse audience, provided readers understand the book’s Evangelical coding.

Some strategies like FIRE and creating employment opportunities are out of reach for most people. Yet, that means Christians with stable professions or higher socioeconomic status have a special role to play: rather than downplay Church teaching to preserve their status, they must (1) be willing to sacrifice, and (2) create the conditions and resource networks that will make sacrifice more attainable and fruitful for their brethren and for themselves. This book makes sense of longstanding, unarticulated cultural undercurrents, and the practical and theological consequences of sacrifice in a post-Christian era will need more unpacking. I hope this book will become one early example among many for reframing this era’s challenges, which are opportunities for honing new leaders and getting Christians of different backgrounds to collaborate for mission.

Aaron Renn, Life in the Negative World: Confronting Challenges in an Anti-Christian Culture. Zondervan, 2024.