Leprosy and legacies

Medicine in Chuuk, Micronesia

“And the priest shall examine him again on the seventh day, and if the diseased area has faded and the disease has not spread in the skin, then the priest shall pronounce him clean; it is only an eruption. And he shall wash his clothes and be clean.” (Leviticus 13:6)

Medicine is a family affair in Chuuk. I’ve spent the first days in the general practice clinic of the only state hospital working side by side with local doctors and our staff. Dr. Tavo is the physician we typically work with. (Tavo is her first name, as all the Chuuk physicians introduce themselves as “doctor” followed by their first names.) A pleasant native Chuukese woman with curly hair and smiley eyes, she has been practicing for about ten years since trying to study a few other fields to escape the family business. Her parents encouraged her to try a non-medical profession, but she found her way back to medicine after seeing her enjoyment matched the needs of the community.

Dr. Tavo typically sees 30+ patients in a typical day. She’s less encumbered by electronic medical records than we tend to be—the doctors in Chuuk just note a working diagnosis and the treatment prescribed in the chart. Still, the patient load is high, especially whenever the doctors are on call for the emergency department or inpatient ward. Dr. Tavo feels bad about turning anyone away since patients often travel to Weno island by boat from other islands.

Some patients also heard the American doctors were also in town and came specifically to be seen. We’ve been instructed to work directly alongside local doctors to build up partner capabilities, so we consult on cases together. We tend to be helpful for antibiotic recommendations, diabetes care, and teaching point of care ultrasound to identify things like hernias, abscesses, and different knee injuries. Dr. Tavo shows us how to treat the parasitic worm infections common in the area and to identify signs of malnutrition.

After lunch one day, we return to clinic to see an older doctor with similar long curly hair, just more grey and with a pensive facial expression. She introduces herself as Dr. Siana, the OBGYN who Dr. Tavo said would be covering while she had an afternoon meeting. Dr. Siana asks how we like working with Dr. Tavo so far, which we answer positively. “She’s my daughter!” she exclaims with pride. When we mention to Dr. Tavo that we met her mother, the younger doctor displays some teenager-like embarrassment.

Dr. Siana is one of two OBGYNs in the state and is having trouble finding a successor, and call shifts can be bad. Some of the doctors mention that their children have gone on to practice medicine, law, or engineering, but have not returned home from abroad. Brain drain is evidently a problem, and lack of private and state funds play a part.

Not-so-rare rare diseases

Another area hit by low funding is the mobile leprosy outreach clinic, but the clinic coordinators are creative. The World Health Organization declared leprosy eradicated based on its low worldwide prevalence, which is the percentage of people in a population who continue to have a disease. Based on leprosy’s WHO designation as eradicated, barely any funding is now available for tracking and treating the disease. Yet, leprosy remains prevalent in many Pacific islands. In Weno island, the doctors report a prevalence of 5 cases per 1,000 people. That high figure grows to 19 per 1,000 when considering Chuuk as a whole, including islands that the team can’t reach as frequently. The leprosy outreach team makes do by combining leprosy work with their tuberculosis work, which is better funded. Their work on both diseases gives them high visibility in the communities.

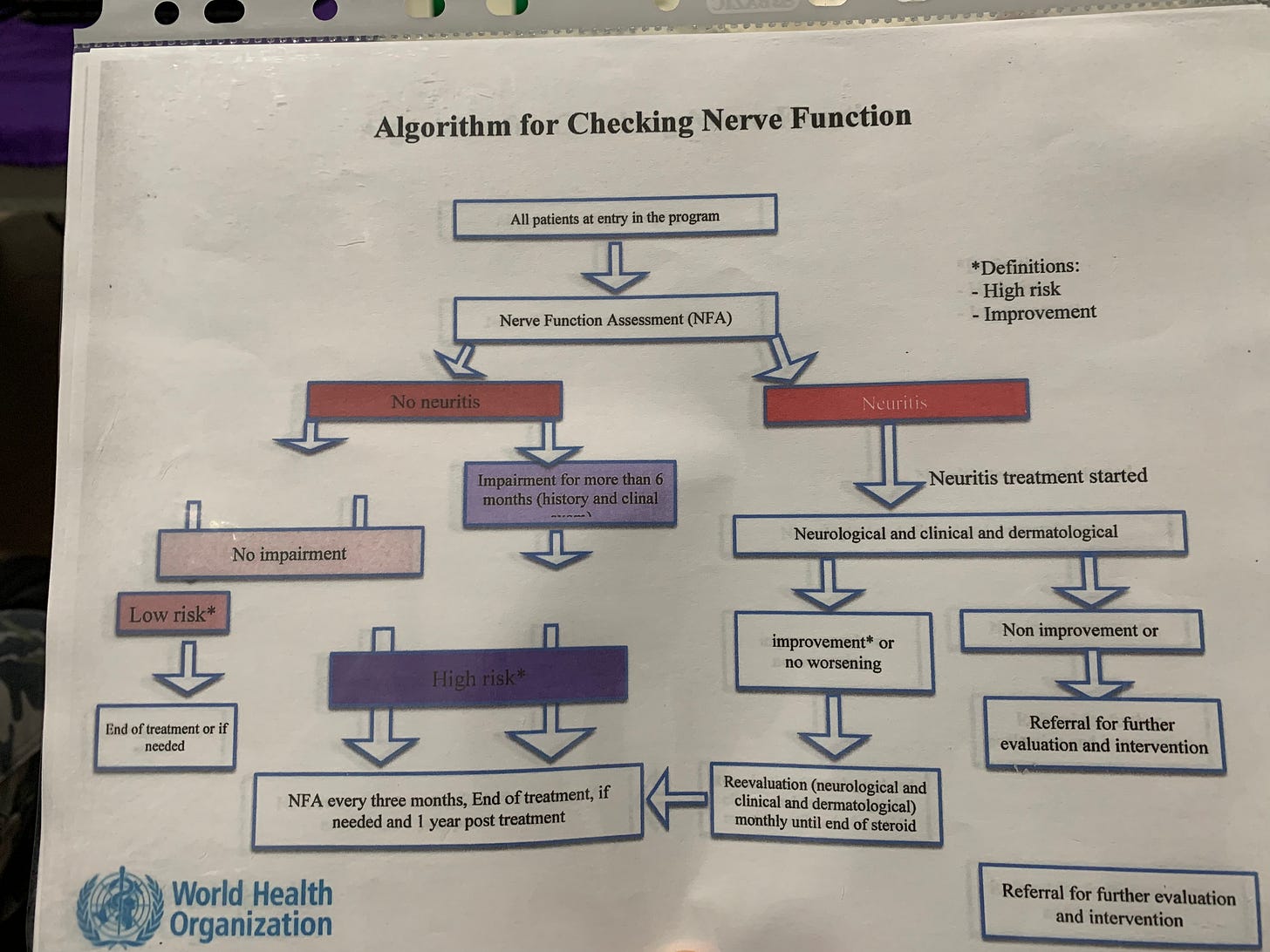

Leprosy, or Hansen disease, is caused by either of two Mycobacterium species, M. leprae and M. lepromatosis. They’re slow-growing bacteria, even slower than Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which means they’re also slow to get rid of. Transmission is thought to be by respiratory droplets over prolonged periods of time, so not through casual contact. Only 3-5% of people without immune problems are susceptible to developing the disease, and it takes 3-5 years for the bacteria to incubate in a colonized host before causing symptoms. For those who develop the disease, disfiguring skin changes occur on the face and throughout the body, along with nerve swelling that weakens the facial and hand muscles. Thankfully, if caught within a few years, the effects can be completely reversed.

The most reliable and practical way to evaluate someone for leprosy is physical exam. The outreach clinic tracks whoever has the disease and their close contacts, especially family members. The outreach teams then visit common areas like churches and schools so these contacts and anyone interested can be evaluated for Hansen disease. The teams go to sites around Weno and take boats to the surrounding islands.

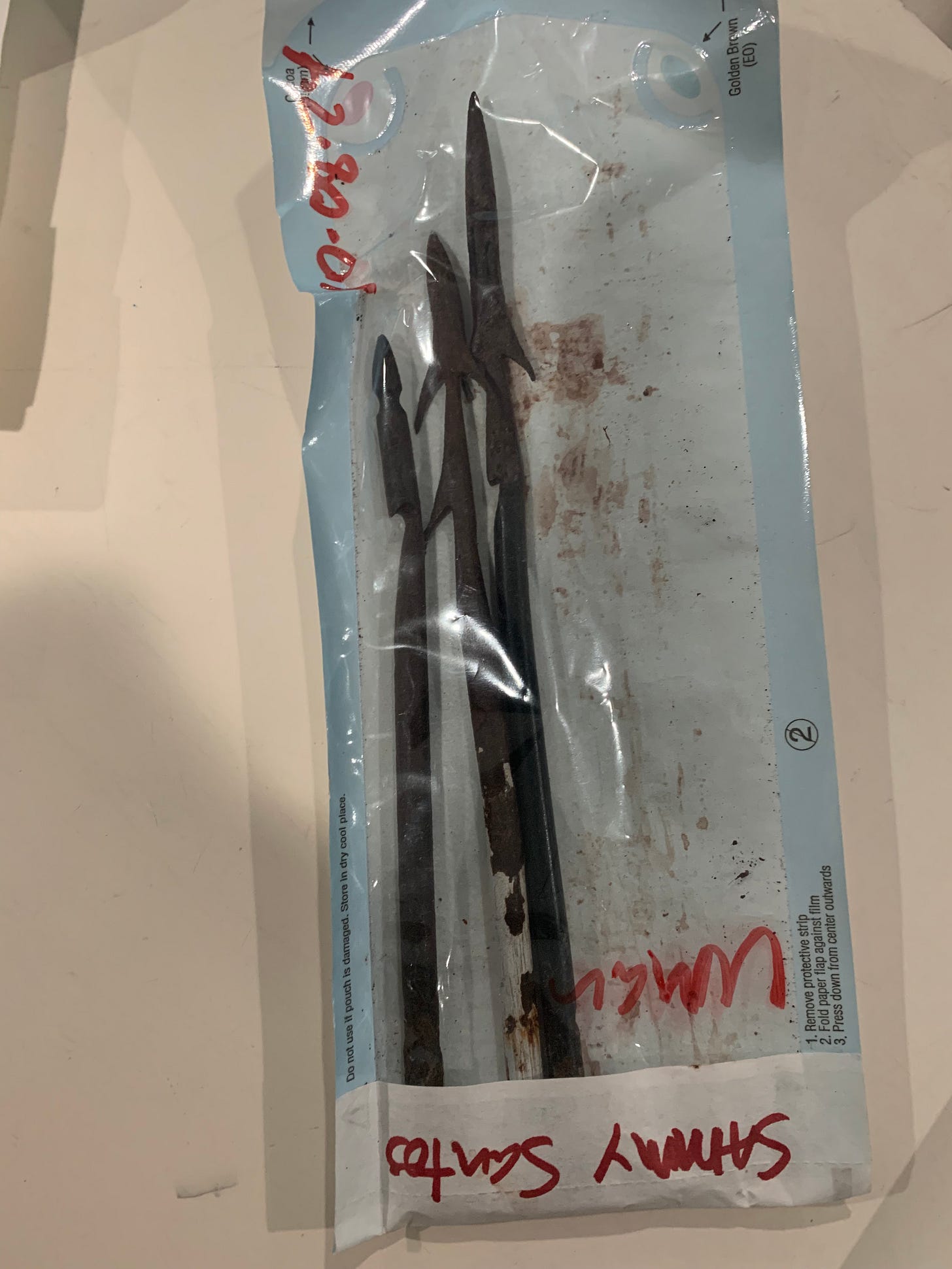

The evaluation includes a skin exam, paying particular attention to the areas behind the ears, on the arms, and on the lower legs where marks first tend to appear. After examining the skin, we test facial, finger, and toe strength and sensation to ensure no nerve injury. People with household exposures are given rifampin, an antibiotic, to prevent developing Hansen disease. The coverage lasts 3-5 years.

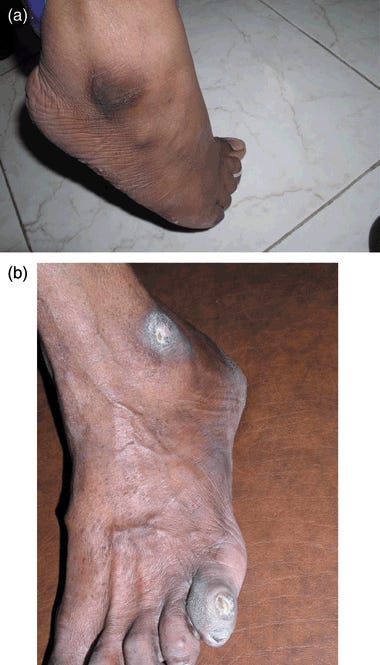

Many of the early skin lesions would seem fungal were it not for loss of sensation over the areas and the way they’re distributed. They first start off lacy and elliptical before causing thickening and knobbly changes to the skin. There are also skin changes that occur with times of increased immune system reaction against the bacteria. We saw this with one of the patients in the hospital.

The acute skin reactions are treatable with oral steroids like prednisone. For the bacteria, patients receive from 6 to 24 months of a triple combination of antibiotics. Some patients stop antibiotics after noticing improved skin after a few months, causing the disease to return with complications. Therefore, the clinic sends public health employees to observe patients taking their medications directly. Patients are even advised to return from travel to receive treatment in Micronesia if they run out of pills, as most doctors in the U.S. aren’t experienced with treating Hansen disease. It’s rare for an American doctor to see it in his lifetime!

One of the two doctors at the leprosy outreach, Dr. Bále, shows us how quickly he distinguishes leprosy lesions from other skin markings. The Chuuk locals have many scars and infected patches on their legs from activities in the forest and rocky beaches. Dr. Bále points out everyday injuries at a glance, sometimes giving topical antibiotics. When I ask him about a blackened area on some of the locals’ ankles, he explains these are calluses from sitting cross-legged on hard ground. This doctor is a charming curmudgeon. When we greet him at 0900 (early for island time), he is eating his breakfast of saimin noodles in the unlit meeting room. “Doctor, why are you eating in the dark? Turn on the lights!” one of the nurses urges. Dr. Bále barely glances up, grunting briefly about how he likes his dark room.

A few days later, Dr. Tavo invites us to dinner in the town. “Did you meet the doctor at the leprosy outreach? He is my father!” I’m only a little surprised this time and joke about her family running a medical mafia on the island. The health of much of the state truly does depend on their work. With local talent emigration, poverty and health literacy issues among the population, and processed foods replacing traditional food culture, they have their work cut out for them.

At dinner, the team exchange gifts with Dr. Tavo and Dr. Siana, including some shell necklaces Dr. Tavo has given us in appreciation of our work alongside her. She also brings her young toddler son, who is wide eyed and friendly.

“Do you think he’ll carry on the family business and be a doctor?”

Dr. Tavo laughs. “We think he will join the military.”

Thanks for sharing about the good work you and your team are doing. I was very interested to read about leprosy and the treatment . What surprised me is that it is still active in different parts of the world. Hopefully the work that you’re doing will help to eliminate this disease.