Meaning and time

Biological clocks and phenomenology

1. Meaning and time. This is the first of my essays directly touching on meaning-making. I’ll define more in-depth what I mean by that activity soon. Basically, it involves determining one’s story relative to whatever constitutes one’s existence. Meaning for humans requires two types of limits. One is my topic this evening, time. The other of course is space—natural space, social, mental, etc.—which is usually easier to discuss.

I’m writing this during a week of ICU night shifts. Consider this a kind of experiment to see how philosophy helps process thoughts and emotions, since night shifts leave a person in a mental fog. If it makes zero sense, please send critiquing memes! Despite being a night owl for writing, I somehow feel groggier at 10PM on night shift than at the same time after an active full day on a normal schedule. But, the feeling helps me consider the function of our internal clocks, which somehow connect our moods to movements of giant rocks and gas in space. Properly connected, the moods rise with the sun. When our clocks are misaligned, then anyone in caffeine withdrawal can tell you the effects.

Why do these connections exist? Objectively, time is a quality of connectedness. It’s the greatest networking tool since the beginning of, well, time. But subjectively, we feel time as a scarce and limiting thing, as contingence. Our measure of time is a measure of dependence on underlying reality and of interdependence with other people and nature. Time affects meaning in our lives depending on how we experience its ties.

The ancient Greeks recognized two of the ways we experience time. The first is chronos, sequential time or the time of duration. This is the time we’re inclined to measure in seconds, hours, days, etc. We experience this time as forward motion. It’s the sense of time associated with death, fate, and the unstoppable process of aging.

The second is kairos, the time of occasions and opportunity, or what the ancients and biblical language describe as the “appointed time.” Kairos ties our actions to meaningful events that form a large part of our life narratives.

Finally, there’s a type of time that’s become easier to recognize these days, which I call anti-kairos. Anti-kairos is time that takes you out of networks of meaning and into cycles of disorientation, and it’s associated with addictions and mood disorders. This will be a subject for another, shorter post. While we can measure chronos, we can’t make it, but we do have a part in creating kairos and anti-kairos. A meaningful life benefits from sharing chronos, creating and recognizing more moments of kairos, and minimizing anti-kairos.

2. Limits are creative substrates, like a canvas or page. Without the limit of the canvas, there’s nothing concrete for an event or narrative to hold onto, nowhere for a paint to stick. So, the limit of time creates the condition for our lives to be stories. The thread of time, woven into a canvas, is a measure of dependence and interdependence in the vertical and horizontal directions. The vertical is where we are relative to the earth and matter as well as to transcendence, like universal truths or our experience of God. The horizontal is relations with other people.

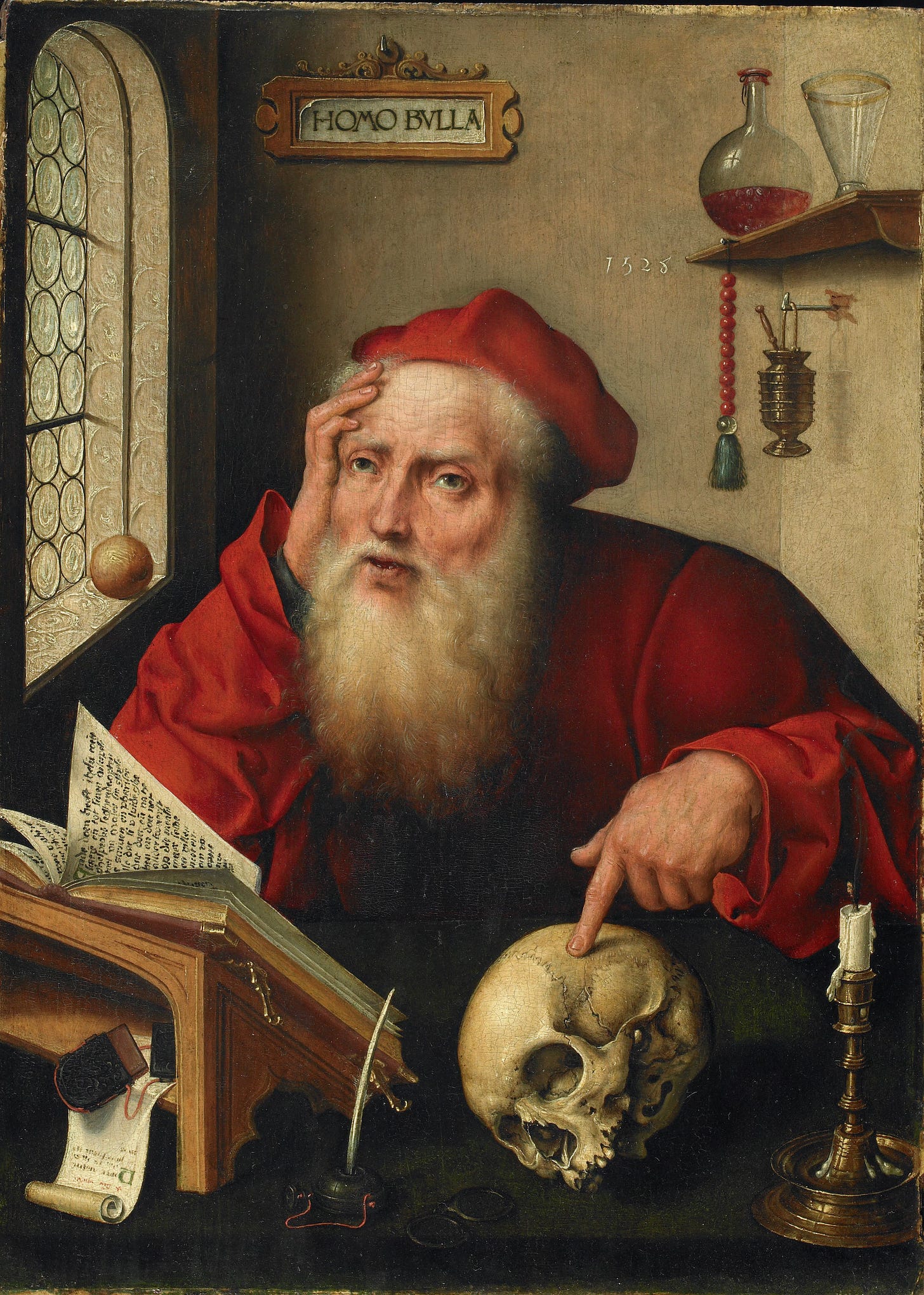

Chronos and kairos are canvas-like substrates for sacred and social moments to emerge. They enable synchronicity: meeting others in time. Time is the condition for care because it eventually leads towards death. Chronos conditions our care for ourselves and for those with whom we share it because it is always towards death, so our limited time with others gains the quality of scarcity. Our being in chronos thus makes us “being towards death,” as Heidegger calls us (Being and Time).

3. Chronos and kairos are morally neutral. But, they determine the magnitude and effect of moral choices. Kairos presents an opportunity, but the combination of your decisions and others’ is what gives the opportunity a moral dimension. Whatever happens in that kairos is still bound to be meaningful to your life narrative. It just won’t necessarily be beneficial! Caesar’s assassination on the Ides of March was certainly an event that had a defining effect on his life narrative. Likewise, saying yes or no to a marriage proposal is your choice, but it will still be a defining event.

4. Bodies naturally track time, both chronos and kairos. Being attentive to the rhythms of the body helps us be aware of kairos emerging from our lives. Time is one reason life, especially human life, is considered in many cultures a reflection of the divine. Naturally alive bodies don’t just move within time. They carry in themselves markers during chronos that become, at periodic intervals, kairos. Therefore, a body can become a site wherein sacred events transform natural processes.

For example, the circadian rhythm is one of the body’s fundamental time measures. (Because it’s preserved at the cellular level and across many species, biology would call a sense of time “well-conserved,” something that’s a commonly expressed trait across time). All cells in our bodies and those of almost every other organism are regulated by a 24-hour cycle. Exposure to specific wavelengths of light from the sun keeps the cycle on track every day, or the internal clock will drift to around 24 and a half hours per cycle. Being just a little out of sync can add up every day, leading to serious problems.

This rhythm gives us one of the most basic natural rituals: greeting the light every day. This is a patterned behavioral response that the patterned structure of the world invites, hence a ritual: “There was evening and there was morning, the first day” (Gen. 1:5). Keeping that ritual is natural. The ritual regulates our moods, makes our sleep efficient, allows us to metabolize food, and is an essential part of our physiologic and social processes. Breaking the ritual by frequently switching sleep-wake times or avoiding light makes us irritable and stressed, leading to poor use of nutrients and fat gain. We further reinforce the natural ritual by designating it as part of sacred time, e.g., through morning and evening prayers that open and close the day with mini-moments of kairos.

Similarly, the seven-day cycle reflects a natural division of time that gives opportunity for kairos. Numerous organ functions and some animal activities appear to follow circaseptan (seven-day) patterns, so that division into seven days is not arbitrary. A natural division of chronos allows us to recognize kairos when we consistently designate a day or days as reflecting certain meanings. Ancient Babylonian and Jewish cultures show the first notable discoveries of the seven-day cycle as a tie between natural and divinely sourced rhythm, most notably with the Sabbath. So, the work week benefits from a motivating structure and moves towards days of rest, family time, or worship. The natural and sacred structures precede the social structure surrounding these days but are also reinforced by the social.

5. Social ties. This social reinforcement brings us to how time ties us to each other, in addition to the cosmos and our sense of the divine. Experiencing natural chronos alongside other people can make the everyday rhythm of life more enjoyable and leads to familiarity with others. Everyday events with another person in time become shared history. Sometimes these natural rhythms become kairos through the presence of others, like dinner with future in-laws or closing a business deal with lunch.

Eating together is a sharing of needs. Synchronizing our internal clocks creates intersubjectivity and togetherness. We all get hungry. Yet, three meals a day aren’t just a suitable convention for nutrition. Meal times enable a unity of our physiologic needs with others’ in time. This time ties groups of people like families together. Like metabolism, shared time extends the effects of the oneish-hour meal throughout social space and the rest of greater time, i.e. the 24-hour day. Hence why the symbolism of missing a meal for work or gaming or trivial pursuits is so damaging to home life and is anti-kairotic.

In those cultures that lack sacred time, tardiness is the worst. Relative to no sacred time, time only has value in terms of intersubjectivity. So, the social dimension of time becomes relatively most important. My time is the most valuable to me, and it gains the impression of greater value by compounding with another’s time. Older cultures with other values around time care less or differently. According to some of my friends, we’re not “late” but rather operating on “minority time!”

6. Social-sacred time. An added social element complicates sacred time. A moment of sacred kairos for a person, like in individual prayer, becomes a larger way of structuring social and even cosmic reality when shared with others. Jewish culture recognizes that sacred activities, shared in time, reverberate the effects of sacred time throughout space and chronos time:

“For in the seventh year there shall be a Sabbath of solemn rest for the land, a Sabbath to the LORD. The land will yield its fruit, and you will eat your fill and dwell in it securely. I will command my blessing on you in the sixth year, so that it will produce a crop sufficient for three years. When you sow in the eighth year, you will be eating some of the old crop; you shall eat the old until the ninth year, when its crop arrives.” (Lev. 25:4,19, 21, 22, regarding Sabbath and Jubilee years.)

Christian culture likewise recognizes this extension of social sacred time through space and ordinary time. Note the words of the Mass: “you never cease to gather a people to yourself, so that from the rising of the sun to its setting a pure sacrifice may be offered to your name (Eucharistic prayer 3),” and, “It is truly right and just, our duty and our salvation, always and everywhere (semper et ubique) to give you thanks.”

The compounded social-sacred effect is a reason why calendars arise as sacred tools in cultures that discover or invent them. Calendars mark common events for the people to celebrate together. Even the French revolutionaries’ calendar was implemented as an (anti-)sacred device. Its twelve months of thirty days each, split into hideous ten-day weeks, facilitated planning holidays such as their Festival of Reason and Festival of the Supreme Being.

7. Closeness and context. With kairos and especially sacred kairos, we gain a sense of cohesion to our lives because these times give us a feeling of context, of being tied to other formative times. The Canadian philosopher Charles Taylor describes kairotic events that reference other events as “closer” in time than chronological time (A Secular Age, 55). For example, your birthday this year refers to the day of your birth. It’s closer to that day all those years ago than it is to any preceding day this year. Similarly, for Catholic and Orthodox Christians, any celebration of the Eucharist is now the closest time to Christ’s Passion two thousand years ago.

These references develop complexity as part of an unfolding narrative, but they aren’t flatly circular, like a repetition of history. Rather, in a good life, the references layer on one another, hopefully in an upwardly spiraling fashion. Note wedding anniversaries.

8. More meaningful time. To maximize meaning in time, respect the body’s rhythms and be mindful of the ways it keeps track of different types of time. Find ways of sharing time, especially biological time. Sharing chronos, including shared measurements of chronos in our bodies, gives a feeling of familiarity with time, surroundings, and others. Literally, familiarity is what leads women to share a time clock when they “sync up.” (Maybe the individualizing effects of the Pill aren’t just socio-psychological or between men and women but also biological and between women and women.) Pubertal rites of passage for young men in most cultures familiarize groups and form identities in a shorter period of time, like a narrative pressure cooker. For our anti-traditional culture, we must either renew or reinvent traditions recognizing defining moments in the body’s time. Traditions recognizing bodily and sacred kairos will help us feel tied together rather than fragmented as bodies, social beings, and story-less characters all running on different timelines.

Life becomes more meaningful the more interconnected and developed one’s threads of time become. Events in which biological, social, and sacred time tie together bring the greatest sense of meaning. When these events connect to similarly layered events later in life, one has a meaningful life. Tying together events happens through references shared between the events themselves and through the events’ effects reverberating in our life narratives.

Love this!!!