Drugs and time

On anti-kairos

Welcome back to my newsletter! Blessed Holy Week, especially to those observing it. This essay connects to my previous post. I’ve also included a few things I’m currently reading or thinking about that I hope you’ll enjoy at the end. I’d appreciate your help sharing the newsletter, or let me know your thoughts in the comments.

For Joe, the best storyteller I know among our peers.

1. Bodies and normal time. Human bodies keep track of natural time and sacred time through our biological rhythms. But there are also addictive time and addictive rhythms that hijack biology.

Classically, humans have thought of time in two ways, as the ancient Greeks described well. It was usually only possible to experience time as chronos, as a linear measured progression, or as kairos, as events that give meaning to one’s life story in a community. Because time is interdependence between natural bodies, time governs us externally as physical contingency and as commitments. Time also governs us internally, as natural compulsions.

The 21st century has brought forth different qualities of time. Only recently have humans and technology become able to hijack internal compulsions on a large scale and alter the quality of time itself. We’ve become able to experience time as non-natural and as non-event on an unprecedented level. I call this type of time anti-kairos.

What characterizes the other two types of time, chronos and kairos, is connected interdependence. The old ties in chronos and kairos connect our internal clocks with either sequential events (chronos) or notable events (kairos) in the world. Internal clocks and good, normal compulsions, i.e. obligations that we feel in our bodies, correspond to real movements. Chronos and kairos tie the functions of the body to social and sacred activities in the world. We all share similar biological and cultural responses to universal chronological events, like the rising and setting of the sun or to the sensation of hunger.

2. Conditions creating anti-kairos. Classic drugs of addiction (e.g. heroin) that produce distinct highs bring about anti-kairos. So do addictions of behavior for things like gambling, pornography, food, and some types of gaming. Finally, some mental disorders like sleep-wake disorders, schizophrenia, and forms of stroke can produce moments of anti-kairos for those suffering them. These conditions are included to highlight our need for building shared time and to understand the different individualizing effects of modern life, not to shame anyone struggling with such issues.

Instead of shared biological and cultural responses, these conditions create individualized feedback loops. Such loops turn a person ever inward. Addictions create cycles of desire and reward that a person only shares with his craving, not even with his self. Normal desires like eating and relationships are put on hold, leading to problems with personal integration.

Other disorders like schizophrenia create internal frames of reference that shrink perception of the world. Some people with schizophrenia experience hyper-consciousness and feel forced to over-consider everything: “levels of consciousness multiply” and create mental paralysis such that automatic actions like moving one’s leg become difficult, as psychiatrist and philosopher Iain McGilchrist notes (The Master and His Emissary, 394). If all moments are equally high-stakes, we have no narrative, no shared experience; moments need variation to be part of a narrative. A plot needs big and small points and highs and lows for comparison.

3. Internal reference. For anti-kairos, the internal clock has no external reference, only an internalized technological reference. Therefore, anti-kairos is a severing of connection. Today, anti-kairos is much more common because we can manufacture new types of unnatural rhythm while removing natural rhythms.

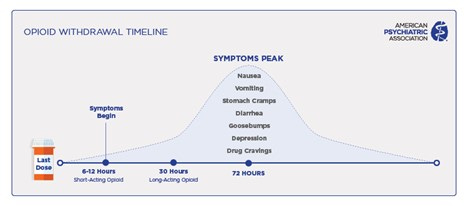

All medications and drugs take a certain amount of time to be processed in the body. They act for a time and then leave the body. We typically measure the time it takes for the latter as a drug’s half-life. Sometimes drugs have withdrawal effects. This timing is a property of the drug and of the person ingesting it, and with addictive drugs and behaviors, a person’s life starts to organize around that property. Time gets measured based on the last hit, the amount of time the high lasts, and how long it will be before cravings come back.

Since these unnatural rhythms are not shared, they take us out of social time. Yet, anti-kairos has an intrinsic and not just social quality of being meaning-emptying. This is because anti-kairos by nature engrosses the attention towards the moment in time as a truncated narrative, as all-there-is. The all-engrossing quality of anti-kairos, coupled with its nature as non-event, means that it stands apart from the life narrative—it feels larger than life when we’re inside of it, but it is really a negation of direction in life. In contrast, during chronos and kairos, one is aware of the context of life around and flowing into that time; the event is something the time has led up to and will move away from. Once the specific time is over, we can put it into perspective as an event that has some effect on our life story.

With anti-kairos, once that seemingly all-encompassing event is over, it fades away, not to be recorded in our meaningful memory. So, the first few times using a drug are kairos—they have a huge role in a person’s life narrative, even if for ill. It is repeated use that begets anti-kairos. Then, using a drug becomes like every other similar moment, every hit of the same drug before it.

4. Internal fulfillment. Like kairos, anti-kairos gives the feeling of being transported out of chronos. Yet, anti-kairotic times have no narrative aspect at all but rather destabilize narrative. Rather than becoming part of a larger life arc, each moment of anti-kairos is its own fulfillment, yet, it is non-fulfillment since the desires are not for real things. This narrative is therefore one of (non-)fulfillment of unreal desires. The fact that this is a narrative is apparent in the neurology accompanying such moments like addictive compulsion: a complete activation of the brain’s dopamine circuits that deal with wanting, seeking, and getting. Through the brain, we experience this whole arc all at once, with no loose ends to tie, except somehow overall unsatisfying. This completeness is one reason why the experience has no place to fit into the rest of our life stories, which are comprised of otherwise incomplete experiences (like chapters with teasers at the end).

5. Narrative challenges. Expect more anti-kairos to be produced before we can minimize it. Factors contributing to anti-kairos are growing. Addictive tendencies arise with increasing fragmentation, fueled by our medicalized and hyper-regulated ways of living. A fragmented, mechanical view of the world is growing. It’s also no wonder schizophrenia is associated with our modern organization of cities. A sense of time controlled by AI will further mechanize our views of the world and ourselves, breaking up our sense of meaning in time. In the world ahead of us, we’ll need the best of storytellers to show the meaning in such flat material.

Reads and mental connections for your enjoyment:

With Ming Wilson and some other friends, I’m doing research on Chinese philosophy and music for a crazy semi-secret project. One interesting find: Chinese worship and speculation of a Supreme Being and source of divinity predate Plato and the West by hundreds of years, explained by the legendary Cantonese scholar Jao Tsung-I.

I gave a bioethics presentation this week on the topic of unexpected death and was reminded of the father of modern medical ethics and medical humanities, Edmund Pellegrino. Maybe someone will take up his canonization cause someday if suitable. Pellegrino was one source of inspiration for the Winged Ox Forum, the Collegium Institute’s theology and medicine seminar group, which I directed in Philly and hope to visit soon!

If you’re interested in an accessible philosophy group, check out this free hybrid seminar on Thomas Aquinas. It’ll be run by my friend Ammar, an accomplished philosopher and young executive from Dallas. I got to witness Ammar’s enthusiasm for philosophy as a social activity when we were Collegium colleagues.

Thanks for reading and staying in touch. If you enjoyed this or think someone you know would be interested in reading, please leave a comment or share this newsletter!